The East Coast Skiff is a 25ft long double ended clinker built rowing boats based on the East Coast of Ireland. It is widely raced by rowing clubs based in coastal communities from Balbriggan in North Co. Dublin to Arklow in South Co. Wicklow. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the skiff was the work horse of the old Hobblers who used to race out to sea off the Dublin & Wicklow coasts in order to meet incoming ships. Their challenge was to be the first one to land their hooks on the inbound vessel where the victorious crew would earn the right to Pilot the vessel into port and win the contract to load / unload the ships’ cargo.

This was an extremely dangerous means of earning a living with crews having to put to sea in often dangerous weather conditions and often having to spend days at a time at sea in open boats with no shelter in order to give themselves the best chance of landing their catch.

With advances in maritime technology in the second half of the 20th century, the Hobblers of old soon found themselves surplus to requirements and the trade of Hobbling soon became but a distant memory.

Although Hobbling faded into the past, the Coastal Communities love of skiff racing continued. The heavy and often unwieldly skiffs of old evolved into racing machines, lighter and sleeker and more suited to racing than the workhorses of old.

As had happened with other branches of Irish Coastal Rowing, competition developed not just in the fitness and skills of the crews but also in the speed and agility of the boats meaning that often races were being won not because the winning crews were faster, stronger and fitter but because their boats were faster, lighter and more seaworthy. The East Coast Rowing Council which is the Class Association of the East Coast Skiff finally said enough was enough and decided to opt for a standard design and ruled that from then on all skiffs built after the introduction of this rule would have to be built in accordance with the stated guidelines.

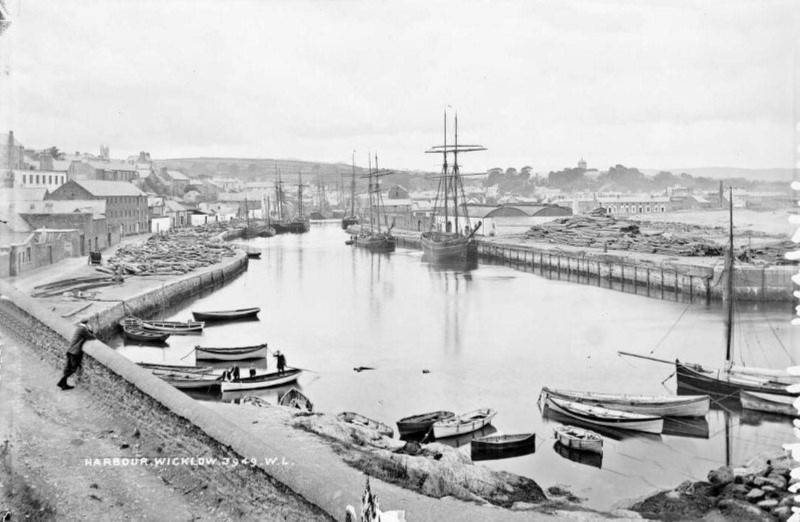

The successful and well proven 1950s built ‘St. Manntan 1’ of Wicklow was chosen as the template upon which all future skiffs would be based upon and a boat builder was drafted in to take detailed measurements and draw up specifications upon which all skiffs would in future be built. Existing boats were permitted to continue racing but all future boats had to be based on this new design.

Remembering the Hobblers’ tales

Apr 17, 2015

https://dublinpeople.com/news/features/articles/2015/04/17/remembering-the-hobblers-tales/

UNTIL the early 20th Century, one of the toughest jobs in Dublin was that of the Hobbler. Strong, sea-faring athletes, the Hobblers acted as freelance navigational pilots for ships entering Dublin Port.

Crews of Hobblers, from Lambay to Wicklow, would row out into Dublin Bay each morning and wait for the sight of a ship. Then the race would begin. The rules of their competition were simple. The first crew to successfully race out and ‘hook’ a ship, won themselves the right to guide that ship safely into port. ‘Hooking a ship’ meant throwing a boat hook up and over its side. There was fierce rivalry between different teams of Hobblers which often lead to arguments about which crew had hooked the ship first. Depending on the size of the ship being led to berth, records show that the successful Hobblers could earn anywhere from £1.50 to £5.

The Hobblers were a key part of many coastal communities across the city. The tradition was very strong in Ringsend and Dun Laoghaire, where several families had produced generations of successful Hobblers. Rowing traditional wooden clinker built boats, known as Skiffs, the Hobblers possessed great skill. The Skiffs were large heavy boats powered by four oars and a removable lugsail that put to sea in all weathers. To move the boat fast enough to ensure their employment, hobblers needed to learn to row in unison, and to take advantage of the wind and tides. It was a dangerous profession that often resulted in tragedy. Many Hobblers couldn’t swim and they rarely carried lifesaving equipment.

On January 23, 1916, two Dun Laoghaire based Hobblers Harry Shorthall and ‘Rover’ Ward were lost at sea. Sixteen years later, on February 22 1928, three Hobblers, also from Dún Laoghaire, were drowned off the Baily Lighthouse in Howth. Their names were Thomas Miller, Richard Brennan and James Pluck. The tragedy occurred at 4.30am, on the dark winter’s night, when the Hobblers’ Skiff was struck by a Dutch steamer, the ‘Hesbaye’. The Skiff had no light and it would have been next to impossible to see from the ship. However, the crew of the steamer heard the screams of the men and launched their lifeboats in a vain effort to save them.

In 1934, Dun Laoghaire was struck by another maritime disaster. On December 5, a local crew of Hobblers were drowned as they returned from a successful day’s work. Rowing their boat ‘The Jealous of Me’ back to Dun Laoghaire, brothers Richard and Henry Shorthall and their friend John Hughes were last sighted at Poolbeg Lighthouse. While it is unclear what happened that night, ‘The Jealous of Me’ was found washed up next morning at Irishtown. One member of the crew survived. Gareth Hughes, John’s brother, had remained in Dublin Port to collect the money owed to the crew. In a further tragic twist of faith, the Shorthall brothers were nephews of Harry Shorthall, the Hobbler who had drowned in 1916.

By the 1940s, Hobbling had declined as means of employment, left behind by advances in marine technology. However, the tradition did not die out. Crews began to organise weekly races against each other every weekend and the victorious crew was often able to earn a lot more than they would have guiding ships.

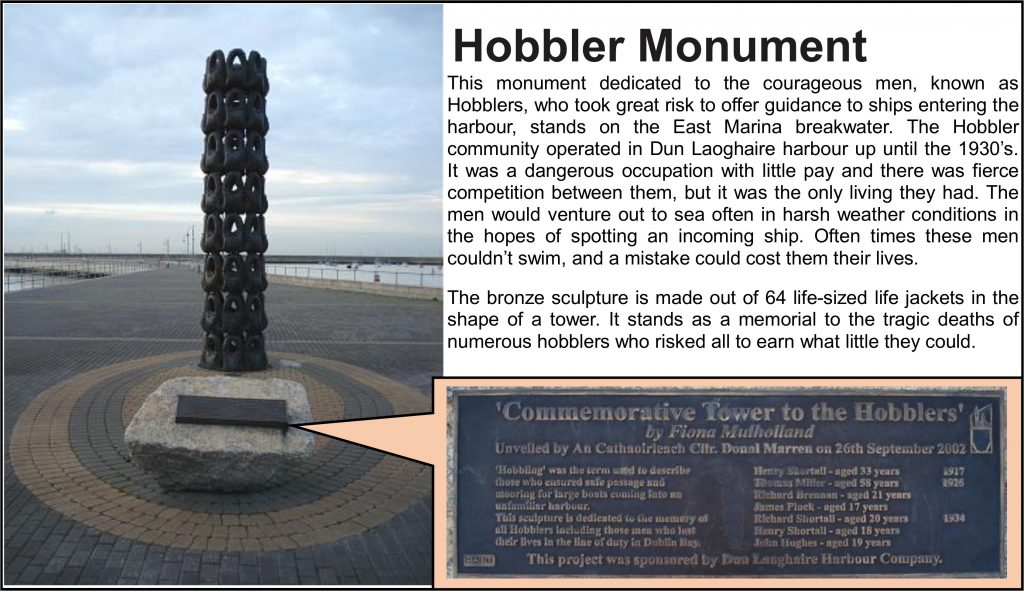

Over the years the Hobblers’ races evolved into the sport of East Coast Skiff Rowing, and the tradition has survived into the 21st century. Today a monument stands in Dun Laoghaire Harbour in testament to the Hobblers and in memory of those lost at sea. These working class heroes knew what it meant to earn a day’s pay!

Hobblers could spend days at sea keeping watch on the horizon to catch first sight of a vessel and once sighted, competing lighters would race to the cargo vessel. First to arrive (securing themselves by hooks to the larger vessel) won the right to board the vessel, carry out negotiations and once a deal was struck, they began the transfer. Discharge at sea was incredibly dangerous and difficult; rolling seas, freezing conditions and high winds combined with the fact the hobblers did not know what cargo they would be handling until arrival at the shipside and invariable it took several trips to complete a discharge, ferrying the goods to Coliemore, Dublin or Ringsend. The level of danger involved was vast and injuries commonplace.

Once the Liffey Channel had been deepened the Hobblers trade developed naturally into pilots and tug boats for the larger vessels guiding them into the Port. While Hobbler crews from Butt Bridge, East Wall and Dun Laoghaire also competed for business, Ringsend was the heartland of the Hobblers so much so they earned the name ‘Gulls of Ringsend’. Kinch, Lawless, Gough and Pullen are all renowned Ringsend Hobbler family names and nicknames of others such as ‘Highwater Flanagan’ ‘Bulletproof Power’ and ‘Bluenose Murphy’’ provide a glimpse of their character.

Hobbling was often combined with other activities such as fishing and as time went on dock working and stevedoring and this evolution probably explains why so few Hobblers are listed in the Census of Ireland returns for 1901 and 1911. At the time conditions in the Dublin Docks were appalling and the role of Dockers in the Lockout of 1913 has been widely documented. One of the Hobblers’ most famous (unverified) claims was in 1919 when Éamon de Valera escaped from Lincoln gaol, boarded a B & I Ferry bound for Dublin but rather than remain on board until the ferry docked and risk capture, he was (reputedly) spirited away by hobblers who went out to meet the boat whilst still under way in Dublin Bay. Later during the Anglo-Irish War of the early 1920s dockers refused to handle munition ships carrying weapons for the British and unloading halted for a time in Dublin, Dun Laoghaire and at other Irish ports.

In the 1930s some thirty competing Hobbler boats were active in Dublin Bay but in 1934 a tragedy involving the drowning of three young hobblers was part of the instigation for a formal prohibition of Hobbling by the Ports and Docks Board in 1936.

No longer active and almost invisible in surviving written records, the real Hobblers never got to sit on the Bench that bears their name today. Its existence however is worthy tribute to generations of courageous men who risked life and limb providing for their families and the city would be the lesser without such curiosities to whet the appetite of any inquisitive passer-by.

Dublin Bay’s Hobblers

Dublin Bay’s hobblers recalled at Dun Laoghaire ceremony

From the 2002/2003 edition of Inis na Mara

More than seven decades after their dangerous enterprise came to an end Dun Laoghaire families with close links to the sea gathered in late September to honour the hobblers.

“The who? ” asked one local teenager when told by a friend that he intended to be present at the dedication in Dun Laoghaire harbour of a compelling monument to the men who years ago guided ships to harbour before the arrival of the Dublin Port pilots.

Skilled men

Councillor Donal Marren, Cathaoirleach of Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council said of the hobblers: “They were men skilled in sailing, courageous men who frequently took risks on dangerous seas, competing against one another and the elements to be first to offer a guiding hand to a ship entering and berthing in harbour. “Their story is a reminder that the poor and humble have had a central role in the history of Dun Laoghaire and must continue to be accommodated within its confines alongside commercial interests and the more affluent in our society.”

Symbol of hope

The monument, commissioned by the Dun Laoghaire Harbour Board, is the creation of artist Fiona Mulholland. It is in the form of a tower of lifejackets suggesting the hazards associated with the sea and the vulnerability of man when faced – with its terrible force. It is in the form of a lighthouse and is a symbol of hope and man’s will to endure and survive, said Councillor Marren.

The pride among the present-day descendants of the hobblers gathered for the ceremony was tangible. They laid wreaths at the foot of the tower and touched with reverence the names of their kinsfolk who had perished in pursuit of their hazardous trade.

Among the lost were young men just out of school and learning their perilous business at the hands of hard fathers and uncles, men with names that currently comprise some of the stoutest and most formidable families in the Dublin districts of Dun Laoghaire and Ringsend, the main centres of the hobbler trade – Lawless, Hughes, Shortall, Miller, Pluck, Brennan.The impressive monument stands on the East Marina breakwater in Dun Laoghaire harbour. On one side is the huge new yacht marina with craft totalling millions of Euro and on the other the grand terminal for the HSS super ferry, all standing testimony to the passage of time, in a sense such a short time ago, and to the advances in shipping generally since the days when hardy men went out in flimsy craft to ply their perilous trade.

The East Coast Rowing Council is the Class Association for the East Coast Skiff.